It goes without saying – nearly every sector globally has been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. But for few sectors are those effects more evident than universities. From admissions to in-person classes to college sports, there’s hardly an element of the experience that hasn’t had to pivot quickly.

So what about endowment investing? As universities face untold economic uncertainties and challenges, what impact has it had on the approach endowments take. Put differently, have the characteristics that make endowment investing different – from time horizons to information access and beyond – been helpful in navigating these new challenges?

Daniel Feder is one to ask. Dan is a Managing Director with the University of Michigan Investment Office and leads the endowment’s investments in private equity and venture capital. Prior to joining Michigan, Dan was the Managing Director of Private Markets at the Washington University Investment Management Company. Previously, among other roles, Feder served asManaging Director of Private Markets for the Sequoia Capital Heritage Fund, Senior Investment Manager in the endowment services area at TIAA-CREF, and Managing Director at Princeton University Investment Company, the investment office for Princeton University’s endowment.

Transcript: Daniel Feder, The State of Endowment Investing

Chris Riback: Dan, thanks for joining me. What's the current state of endowment investing?

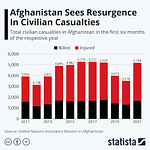

Dan Feder: Well, before I get into it, I just want to make sure, just say one thing, which is, I think is really important. The world in which we're talking about, which is endowment investing is just a very small corner of the world. It's a very small corner of the economic markets and it's a very small corner of what's going on generally. I just feel like I would be reminiscent, not just mentioning the fact that the loss of lives, the impact on lives, livelihoods relationships, access to healthcare, mental health education, and really every facet of life, that we're navigating right now, as a result of the impact of COVID-19 or just, front and center. The question around what's the impact, or what's the state of endowment investing today. I want to just make sure that I put that in proper context.

Chris Riback: Indeed, nearly everything these days needs to have a context and perspective and thank you for providing something.

Dan Feder: Certainly, I feel like what we do in managing an endowment at the university of Michigan I'm sure anyone who manages endowments, feels the same way, which is this is important work because we're supporting institutions that are very important, especially today. And so the state of endowment investing today in many ways, is really the same as it ever was. We have the same objectives that we've had all as always, the investment model or the endowment model, is more or less the same with a very large caveat attached to that, which is there is no single endowment model of investing.

We have the same objectives for the most part, and those are maintaining purchasing power of our institutions, providing some investment gains to support spending at the institutions and if we do a good job providing a real return above spending and purchasing power, if we can. So in many ways the state of endowment investing today is really the same as it ever was. The events of COVID-19 and the impact of COVID-19 have changed some things in very important ways. One of the things that it has changed or created a heightened awareness about is the fact that all colleges and universities are not the same operating businesses.

They don't operate in the same way. If we look back over the past 20 years, we've had, now this is our third major dislocation. We had the TMT bust in 2000, and then we had the global financial crisis in 2008 up to 2009. Now we have, and we continue to have the dislocations related to the COVID-19 pandemic. I know it's dangerous to say this time is different because whenever someone says something like that, they're proved wrong, but I really do think this is different in some important ways. Those prior two dislocations were really about what happened in the financial markets and what's happening today is a terrible set of events that are having a great impact on the real economy, not just the capital markets. That is especially true when we look at the impact on the dominance and more broadly on the institutions that we support, the colleges and universities for whom we work.

Chris Riback: Why is that? Why do the real economy effects have a bigger impact than just market effects?

Dan Feder: Because this is what happens in real life. At a college or university, one thing that colleges and universities have in common is that we are gathering businesses. We put people together in many different ways. We put them together in classrooms and dormitories and research facilities and hospitals and fraternities and sports venues, and the activities that happen on the campus of a large research university are very different than what takes place at a small liberal arts college. The activities in a college, a university that's located in a rural area are very different from a one that's located in an urban area and so forth. And so that really, it doesn't trickle down, it's part of what we do as an endowment and in those prior to dislocations, we were all more or less effected in similar ways, but in this one, the actual activities and the business that takes place on a college or university campus, the impacts have just been very different across institutions.

Chris Riback: I know that that occurs. And you mentioned it that occurs in every aspect of the university life in the classrooms, in the neighboring businesses, but, just being very focused on where you are and what institution you work at, is there a more visual representation of the impact than seeing what feels like a couple of hundred people sitting in the big house in Michigan Stadium for the football games? I mean, watching it on TV, it is so stuck and it's not the only place, obviously it's basically every stadium that we look at. But, given the fact that you are at University of Michigan, that stadium is such an iconic place. I've seen it a few times on TV. That is just a visual reminder of exactly what you're talking about.

Dan Feder: Yes, it certainly, as the absence of that activity is tangible and on a day-to-day basis. When I go out for a run in Ann Arbor, I see it every time I go outside and especially if I run anywhere near where the medical center is. It's just a really stark reminder of what it is that's going on here. What it is we're facing when you go past or around a medical facility or through the center of town, which is empty or on a Saturday when there is supposed to be a game and nobody's around, those are all great and important, tangible reminders, they are reminders of things that we ought to have in mind, day-to-day, as we manage an endowment and going from the kind of the 20,000 foot or 30,000 foot level down to the very granular of what happens or how we think about investing an endowment program.

The fact that the activities on campus, from one university to another one college to another are different, do serve as a reminder or reminders that the way we invest also ought to reflect the institution in many ways.

3 Advantages in Capital Markets

Chris Riback: How do you mean?

Dan Feder: In portfolio management, one way, that I think is really important is that colleges and universities generally have the same three advantages in capital markets. And those three advantages are an ability to have a long time horizon. We have access to information and people that is differentiated from other institutional investors, and we have access to opportunities that are unique to our institutions, and it is important to keep those in mind I think in how we go about investing and how we go about designing our portfolios, because having even a single advantage in the capital markets is just a great and valuable thing, and we have three of them.

We ought to be thinking about how do we apply those advantages in a way that can advance those three objectives of our investment programs in the greatest way possible. Just to bring some, I guess, context to that, in the case of a large research university, we have by definition, a lot of research, a lot of innovation going on here at campus. We invest in venture capital funds, and we hope we're investing with the very best, VCs in the industry. And we can make ourselves a better partner to those VCs by creating connectivity between what happens here on campus, in the area of research or in tech transfer with what our partners are trying to do as investors. That kind of connectivity works or can work in really powerful ways in both directions and it puts us in a position where we can have access to investment opportunities that other institutions don't have, and it gives us insights into markets that others simply don't have.

How do we apply those and where do we apply those and where can we get the greatest bang for the buck, so to speak in going after opportunities where we can make returns that are maybe not generally available or just hard to achieve, by institutional investors. That really does speak though, to what are the unique attributes of each of our institutions in doing that.

Chris Riback: Are the advantages even greater now, or are they somehow diminished slightly because of the crisis?

Dan Feder: The advantages that I outlined, were clearly there before the COVID pandemic. They were there before the global financial crisis, and they were there before the TMT bust. I think the change is how we go about applying those or the impact is how we can go about applying those to what we do day to day. I think, on balanced. It may sound naive to say so, but I don't think that they've changed all that much.

I think that perhaps we have a greater awareness of the role of our institutions in how we go about forming our portfolios and managing them. That may be, it's very small silver lining to a cloud. I mean, this is not a case where, the silver lining is as large as the cloud. This is a case where the silver linings are way smaller than the size of the cloud. But one of the positives that we're observing right now is the fact that we work, with the university, around, how all this comes together, how it all fits together is something that is just really important. It's not something we've lost sight of, but it's something that is taken on just a massive importance.

I think it's just a very small silver lining to this cloud that, going forward, there's, I would think there'll be more integration, more dialogue across institutions, not just ours, but all colleges and universities about how endowments and endowment, like assets of universities and colleges fit together with working capital and tuition in flows and research dollar in inflows and so forth.

Pressure-Testing Governance

Chris Riback: What about governance? How has the pandemic added anything to your governance process, your approach, have you had to consider it differently or from the different perspective, has it proven out, have you kind of felt helpfully, "Wow, we had pretty good governance in place and it was in place exactly for circumstances like this?"

Dan Feder: I can only speak from the perspective of where I sit and, you know, without a doubt, the COVID-19 crisis is pressure tested any number of aspects of how we do business at a university, and certainly how we do business as an endowment. And we're just very fortunate and I can speak to our experience here, but one of the things that really drew me to endowment investing in the first place was exactly the topic of governance. And if done properly, endowments and foundations are really, in a special place, with respect to doing investing well, we have far fewer agency issues than you would expect to see at a corporate investor or any place where interests of the individuals can override the interest of the institution.

We have people around the program, whether they are advisors or alums, or have people within the administration and people within the investment office who are involved because they really do have a deep affinity and a lot of, sort of personal reward wrapped up in the success of the institution. And so when you have that, it really helps clarify how you make decisions and it makes, investment decisions a lot more rational and sensible than you might see in places that have more agency issues running around them.

Chris Riback: What about sector views? Do you have a stronger affection for interest in various sectors? Has that changed as a result of the crisis or are you kind of sector neutral? And instead you look to utilize, leverage the advantages that you spoke about earlier, regardless of what sector that impacts?

Dan Feder: Well across an endowment we can't, or we shouldn't have a point of view that one sector or another is going to dominate everything else. We want to have a diversified portfolio. We want to have a number of drivers of return that allow us to have both intergenerational equity with respect to spending and support of the university, while also generating returns that some sense we should have less sensitivity around volatility for there are segments of the portfolio where sectors do figure more prominently and they are in the areas where we do much more bottom up or bottom up oriented investing and the clearest cases that would be in venture capital, I think, so in the case of venture capital, we are in the midst, I believe, and we can debate this, but I think the facts are fairly compelling around it, that we are in the midst of something that feels like an industrial revolution.

It's a technology driven industrial revolution. In the venture capital part of the portfolio, we are trying to invest into that in very real ways and this goes also back to some of our advantages. I think that we have as an investor. So as a research university where we have access to world-class individuals in the research function, through our tech transfer across the university, we have an ability to diligence ideas. We also have a vast network of loyal alums and networks of people who come from our business partners, meaning our firm managers that, can help us navigate places to invest that we think are really compelling in a very much, a bottom up way.

Some of the areas that have been really productive for us and I think are going to be hugely productive going forward, involve, new advances around drug discovery and life sciences, advances, we've made some investments that way too early to declare victory or defeat, but I think we're positioned extremely well and we're positioned extremely well because we have an ability to think about these things in a bottom up way. That makes a lot of sense and then I guess more broadly, we think opportunistically, especially in the area of the portfolios, I said that, probably more over on the private equity and venture side where we're much more bottom up, but we think opportunistically across the portfolio and things just come our way.

I guess, because we look for them, but also because, they do come our way and it can come in any number of packages and that can be a little bit from anywhere, but, so not sector specific, but I'd say, one area where we really do have a conscious effort in terms of sectors around technology and innovation. Especially in the venture end of the portfolio, that's where we really want to be long innovation.

Chris Riback: Well, it makes sense for all sorts of reasons, including of course, one of those advantages you mentioned, that the access to cutting edge ideas and insights that would come from a university and the university of like university of Michigan. I just want to be really clear though, on one point that you made earlier, Dan, under no circumstances, would I be looking to debate with you in the first place? I would simply lose, so that's not something I would ever even think about doing thank you for the warning, but to your specific point, I would never even debate that. I totally agree. It does feel like an industrial revolution as opposed to a debate that that actually might be something for a future conversation, because we're in the middle of a massive change. Aren't we?

Dan Feder: I think, well, I'm convinced we are one of our partners, one of our venture capital fund managers, had a little snippet that I thought was really interesting. And he said that, during the industrial revolution that we would refer to, or when the electric electrification of industry was taking place, there were people in companies called chief electrical officers, and we don't have that anymore. Now we have chief technology officers and this point was we look forward a bit we probably won't have chief technology officers that will just be part of what we do, and it is part of what we do.

It's not different this time. It's, there's an innovation cycle that's happening right now. And the mount of innovation and the amount of disruption that's occurring right now is formidable. It's exciting. It's also a little bit scary in some ways, but it is exciting as an investor.

“Investing into Uncertainty”

Chris Riback: Two thoughts to start to close out the conversation. One is picking up on the point that you just were making, you have spoken previously, you have written previously about the benefits of investing into uncertainty. Of course, part of me wonders if you want to be careful what you ask for we've had plenty of uncertainty, but would you explain again, your philosophy for listeners and tell us how it's currently holding up?

Dan Feder: Well, I'd love to explain my thesis, but my thesis is really stolen from an economist named Frank Knight. So I've got to give credit where credit is due. Frank Knight in the early 1900s wrote a dissertation for economics PhD, which is now published as a book called, "Risk uncertainty and profit." The proposition there is that there is a big difference between risk and uncertainty. Uncertainty is really the realm of things that are not known and are not knowable and risk relates to looking at data sets or information from the past and creating a point of view of the future and what the power of uncertainty provides, I think is that if one is able to invest into conditions in which others don't know something and can't know them and can do so well and consistently that durable profits ought to result.

So what does that mean in the realm of venture capital? It means that if you are a venture capitalist and you have access to an entrepreneur or a founder, who's come up with a business idea or an innovation that is not known to the rest of the world and is not knowable to the rest of the world and you as a venture capitalist are able to invest sensibly in that idea, and you can do that sort of thing repeatedly. Then you ought to have the opportunity to generate real economic profit on a consistent basis. And that's what we're trying to do in the realm of venture capital.

It's what I try to do when we're investing in areas where we can put those three advantages that an endowment or an endowment related to a college or university has, which are access to information and access to people, that others don't have and where time horizon comes into play with all that is that when we invest into those sorts of opportunities, they are by definition illiquid, they have to be. If something is not understood or the attributes of that investment are not really knowable, and it will take time for the goodness of those ideas to become known or knowable by others.

Well, they are illiquid until that happens. The idea of investing into uncertainty, I think it's just very powerful. We have a lot of uncertainty in the world right now and I certainly wouldn't advocate investing into those realms, because we don't have any advantages in understanding what's happening. We do have some advantages in understanding uncertainty better than others in some areas and that's where I try to focus some of my time and attention, particularly in private equity and venture capital.

Looking to 2021

Chris Riback: To close out, Dan, as you do look towards 2021, how are you framing your thinking? Is there anything that you are viewing opportunistically, any risks that we haven't discussed, that you are particularly wary of? How do you view the year?

Dan Feder: Well, I'll tell you one thing that does worry me and it's ketchup. It's ketchup because when I was growing up, there was ad campaign that Heinz had on television, for its ketchup and the tagline of it was anticipation. The idea was that, you turn this ketchup bottle over. If it's a high quality ketchup, made by Heinz, it would take a long time to come out and it's okay. Because anticipation is a wonderful thing. If what comes out is-

Chris Riback: Is as delicious as Heinz ketchup. I understand.

Dan Feder: So, why do I worry about ketchup? Well, we've had a really good run in some areas of the portfolio and especially in venture capital and in technology based businesses that have stayed private for a long time. They've developed in many cases into becoming really substantial businesses. But they're illiquid and we have more and more of those, and we have a backlog of those and those are the ketchup in our bottle. The problem is, and the thing that I worry about is the aperture of the opening just doesn't change and we're happy to take a long term view of things and be illiquid up to a point. But I do worry that if we get too much ketchup in the bottle it's going to be a problem. We can shake the bottle and we can do all sorts of stuff to try to get the ketchup out, but the opening stays the same size and even banging on the number 57, which is supposed to be the magical thing.

Chris Riback: It's the key, I've won plenty of bats by banging on the 57 on the side of a Heinz ketchup bottle.

Dan Feder: But what does worry me a bit is that we get a backup of things that really ought to become liquid, and that exercise in and of itself in how things become liquid, how value is realized, is important. If there's anything that's on my mind right now, it's how do we manage the portfolio, in parallel with this process of seeing good companies and great companies become public or become acquired so we have room to make more investments so that we can participate in what we think are great opportunities where we can be long innovation. Again.

Chris Riback: Do you have any finger on the pulse as you look at IPO offerings, any acquisitions that are kind of occurring the pace of things over the last weeks and anything you're hearing in terms of maybe Q1, anything that's giving you a sense of the finger on the pulse of that pace?

Dan Feder: Nothing that's unique, other than to say that a lot of people in the market think that the opportunity to get companies public one way or the other, or realize value, if there's a lot of depth to that. I think there is a lot of depth to that, but, up to a point, so I'm not by my comments, I'm not trying to leave you with the impression that I think we're in a lot of trouble. I just worry that, we do perhaps had too much of a good thing in terms of there are companies that are on the precipice of becoming public or where we can start realizing some of our value.

Chris Riback: Excellent. Well we'll look forward to that. We will see what happens, and we will all keep banging on the 57 of the Heinz ketchup bottle and hope that it brings the rewards that sit inside the bottle. Dan, thank you. Thank you for your time. Thank you for your views. And thank you for sharing all of that with us.

Dan Feder: Well, thanks for making time to speak with me. It's been a real pleasure.

Podcast: The State of Endowment Investing -- Daniel Feder, University of Michigan